What kind of man was Guy de Maupassant?

- rosalindodowd

- Aug 4

- 4 min read

What kind of man was Guy de Maupassant? The question seems to have vexed Maupassant himself almost as much as it has exercised the minds of critics and scholars since his death from syphilis in 1893, one month before his forty-third birthday. For more than a hundred years people have disagreed about the complex personality behind the six novels and some three-hundred short stories which are now universally admired.

For some Maupassant was the sensualist with an austere talent, a man at once "so licentious and so impeccable"; for others he was "courageous", possessed of a profoundly "compassionate heart," who yet had no morals, "an absence of scruple" - a "born sadist" with "an eye of profound pity".

Maupassant felt strongly that an artist's work should be enough for the public; there was no need for his person also; but in his sailing journal, published in English as Afloat and containing the true story upon which The Hidden Lovers is based, he explored his own troubled and divided personality more revealingly than perhaps anywhere else in his work.

His, is an acute example of a sensibility surely common to many artists but perhaps especially to many writers - a sensibility which feels intensely and yet is, paradoxically, somehow detached, a sensibility prone to almost disabling empathy which yet compulsively observes, analyses and reflects. "We should not be envied, but pitied, for this is how a man of letters differs from his fellow men . . . In him, no simple feeling exists anymore."

Everything he sees, his joys, his pleasures, his pain, his despair, instantly become subjects for observation. He analyses in spite of everything, in spite of himself . . . If he suffers, he makes a note of his pain and files it in his memory . . . Above all he is a man of letters and his mind is formed in such a way that to him the repercussions are much sharper . . . than the first knock, the echo more resounding than the original sound . . . He seems to have two minds . . . condemned to watch himself feel, act, love, think, suffer, and never to suffer, think, love, feel like everyone else does, kindly, truly, simply, without self-analysis . . . He suffers from a strange ailment, a sort of dividing of the mind, which makes him into a frighteningly impassioned, calculating, complex creature, who is exhausting for himself."

It might be pointed out that the fact these intensely personal reflections are themselves written in the third person makes them a perfect emblem of what their author is trying so anxiously to convey.

A somewhat ghastly portrait of Maupassant is to be found in The Story of San Michele, the celebrated memoir of the Swedish doctor Axel Munthe; my hopeful suspicion is that the portrait is somewhat more highly-coloured than the original warranted, but there are surely more than a few grains of truth in it. "We used to have endless talks on hypnotism and all sorts of mental troubles, he never tired of trying to draw from me what little I knew on these subjects," writes Munthe. "He also wanted to know everything about insanity . . . I well remember our sitting up the whole night talking about death in the little saloon of his Bel Ami riding at her anchor off Antibes harbour. He was afraid of death. He said the thought of death was seldom out of his mind. He wanted to know about all the various poisons, their rapidity of action and their relative painlessness.

He was particularly insistent in questioning me about death at sea . . . 'No', he said at last, he thought after all he wanted to die in the arms of a woman. I told him at the rate he was going he had a fair chance to see his wish fulfilled. As I spoke Yvonne woke up, asked half dazed for another glass of champagne and fell asleep again, her head on his lap. She was a ballet dancer, barely eighteen . . now helplessly drifting to destruction on board the Bel Ami . . . I knew that she had given her heart as well as her body to this insatiable male . . . How far he was responsible for his doings is another question. The fear that haunted his restless brain day and night was already visible in his eyes. I for one considered him already then as a doomed man. I knew that the subtle poison . . . had already begun its work of destruction in this magnificent brain.

Did he know it himself? I often thought he did. The MS. of his Sur l'Eau was lying on the table between us, he had just read me a few chapters, the best thing he had ever written I thought. He was still producing with feverish haste one masterpiece after another, slashing his excited brain with champagne, ether and drugs of all sorts. Women after women in endless succession hastened the destruction, women recruited from all quarters, from Faubourg St. Germain to the Boulevards, actresses, ballet-dancers, midinettes, grisettes, common prostitutes - 'le taureau triste' his friends used to call him. "

Munthe's portrait ends with their last meeting, in the garden of the asylum Maison Blanche in Passy. "He was walking about on the arm of his faithful Francois, throwing small pebbles on the flower beds with the geste of Millet's Semeur. 'Look, look' he said, 'they will all come up as little Maupassants in the spring if only it will rain.'"

*** *** ***

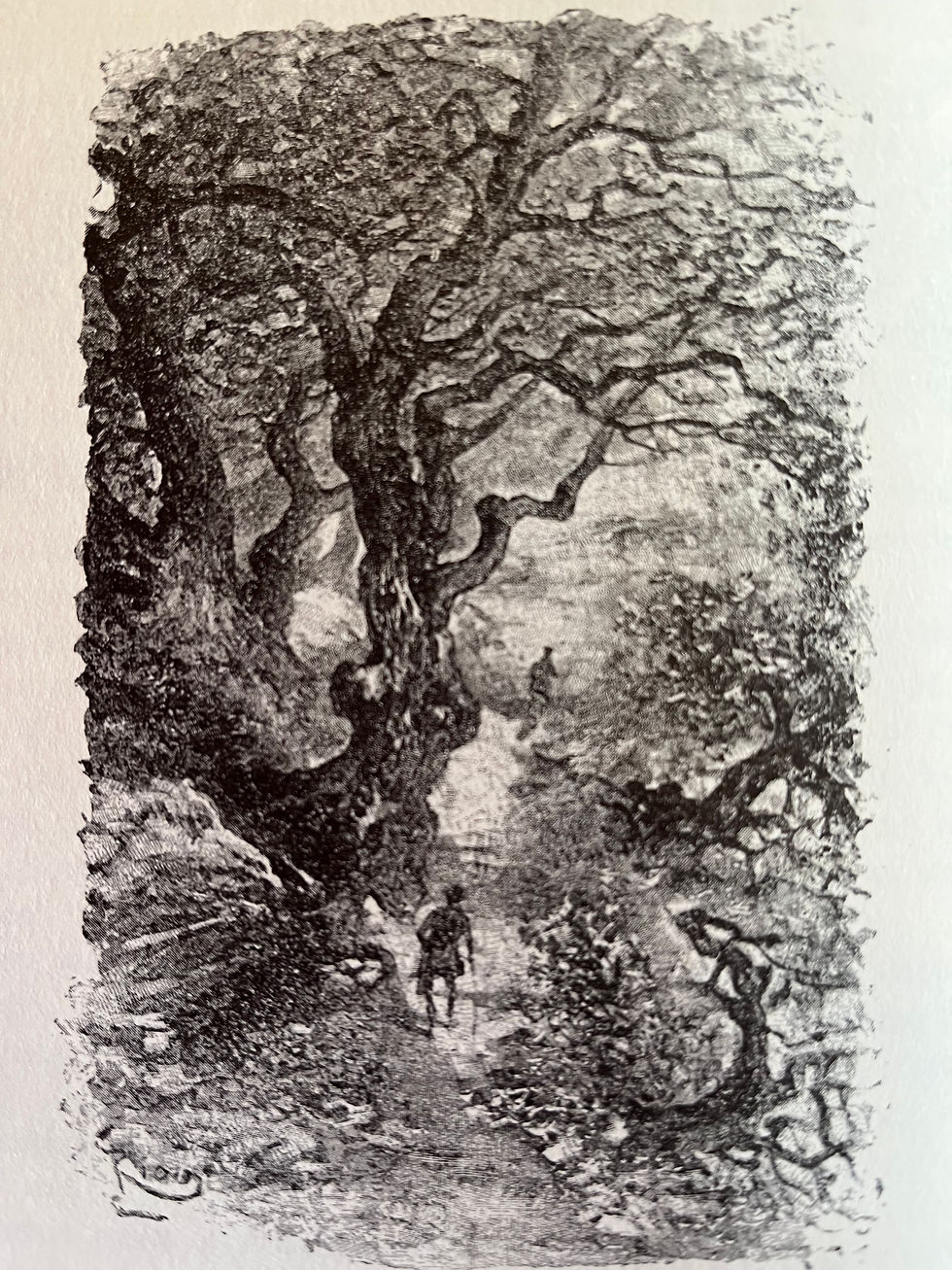

The Traveller in The Hidden Lovers is by no means a portrait of Maupassant but the character does draw heavily on the French writer's conflicted, sensual and melancholic nature - the sophisticated metropolitan who yet longs for simplicity and purity of feeling - and above all on his extreme ambivalence - fascinated and repelled, admiring and contemptuous, envious and doubting - in response to the story of the husband and wife who, hidden from the world, have been everything to each other.

Simon Pettifar

Comments